Earlier today, it began to rain heavily at the office. Naturally, the first thing we did was to check our Miri App (currently in beta testing). To my surprise and disappointment, the forecast on the app confidently shows sunny and partly cloudy.

We were fairly confident this wasn’t a programming error or glitch, so we checked our forecasting models and none of them had predicted the rain.

The problem of unreliable weather forecast

I bet you have experienced this once, and you may have felt the same disappointment. Unfortunately, this inaccuracy is the reason several people believe that weather forecasting is a comedy of errors.

Despite its challenges, weather forecasting remains one of the most important scientific tools shaping modern life and influencing everything from flight planning to agriculture to launching a rocket into space. Yet, it struggles with accuracy, especially in regions like Africa.

Why can weather forecasting feel inaccurate?

Weather forecasts can appear wrong not because meteorologists are careless, but because of several other factors, which may include

- The atmosphere is a chaotic and complex system, making long-term prediction inherently difficult due to the sensitive dependence on initial conditions. A tiny change in humidity or temperature of one area can trigger a completely different outcome somewhere else.

- Forecast models rely on equations and assumptions. They simplify reality, so some weather patterns, especially fast-changing ones, are harder to capture.

- Some weather events are hyper-local. Thunderstorms, sea breezes, and late-season showers can form suddenly over very small areas. Many models simply cannot detect these micro-scale triggers.

- Satellites operate at a resolution which may not capture lower atmospheric processes and leaves out hyper-local realities.

How are forecasts actually made?

Weather forecasting begins with data. Meteorologists collect climate and weather observations collected from satellites and feed them into predictive models, which are mathematical equations designed to simulate atmospheric behaviour.

These models, however, have a key limitation: the resolution of satellite data may not capture low-level atmospheric processes, leaving out hyper-local conditions. As a result, hyperlocal, short-lived events, such as pre-monsoon or late-season showers, can sometimes occur without appearing in the forecast.

When satellite data does not capture these smaller, near-surface events, the models cannot predict them accurately. This does not mean the model is wrong; it indicates the need for more detailed ground-based observations.

Ground-Truth Data changes Everything

While satellite data provide wide spatio-temporal coverage, ground truth data provide hyperlocal measurements that capture near-surface atmospheric phenomena. Numerous studies (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6) have shown that the integration of in situ data from weather stations and sensors with satellite data improves resolution and enhances forecast accuracy.

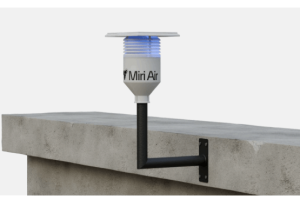

This emphasises the importance of our work at Climate in Africa. At the core of our mission is to build a continent-wide network of Miri Air stations that will deliver high-resolution environmental data in real time across every African street.

Weather forecasting will always be a balance between science and uncertainty, but uncertainty reduces drastically when better data feeds the models.